Colophon

Matariki | |

|---|---|

| In this EBook we discuss the heliacal rising of the open star cluster Pleiades and how that relates to the New Year celebrations of the New Zealand Māori | |

| Tags | Astronomy, heliacal rising, Pleiades, M45, Atlas, Pleione, Matariki, Mata a Ariki, Māori, new year, mid winter, solar day, sidereal day, lunar calendar, Puanga, Rigel, Tangata Whenua, Te Tou Hou, mihi maumahara, Pākehā, |

| Prerequisites | |

| Author(s) | EV |

| First Published | May 2009 |

| This Edition - 3.2 | June 2021 |

| Copyright |

|

Introduction

No Calendar![]() For millennia humans have lived without a calendar as we know it. There was no way to tell one day from another, one could only observe the slow progression of the seasons. The lunar cycle has often been of great importance for providing key times for spiritual and practical activities, but the lunar cycle is at odds with the annual cycle. There is not a whole number of lunar cycles in one annual cycle.

For millennia humans have lived without a calendar as we know it. There was no way to tell one day from another, one could only observe the slow progression of the seasons. The lunar cycle has often been of great importance for providing key times for spiritual and practical activities, but the lunar cycle is at odds with the annual cycle. There is not a whole number of lunar cycles in one annual cycle.

For us in the 21st century it is hard to imagine that it hasn't always be normal to say “today is the 16th of March” or “ we will meet on October 13th ” and then knowing precisely which day you mean.

Natural “clocks” are the day and night cycle, the Moon cycle and the seasons. But especially these last, the seasons, could not be accurately defined. Nature told you a lot, but never precise. There was a need for some accurate reference points throughout the year. This was important for agriculture (readying the land, sowing, caring for the crops and harvesting and animal behaviour for hunting, etc.). There also was a need for the spiritual side, knowing when it was the right time for certain celebrations, offerings, etc.

Hongi. Credit: students.stedwards.edu

Hongi. Credit: students.stedwards.edu

Astronomy has provided techniques and methods for this since ancient times. In this module we will explain the astronomical background of a technique called heliacal rising to define a particular time of year, and make reference to the way the Tangata Whenua in New Zealand traditionally define and celebrate the New Year.

The Role of Astronomy

Sumerian astronomers. Cylinder seal, about 3500 BC

Sumerian astronomers. Cylinder seal, about 3500 BC

Credit: edwardtbabinski.us Astronomy is one of the oldest sciences, although the term science has only been in use since the 17th century when Descartes defined the principle of dualism, essentially separating religion and science. As a philosophy, astronomy (astrologia) has dealt with the definition of calendar and time systems for practical and religious purposes, the prediction of stellar positions (to be used in astrology), but also had the task to make predictions about the future, and to explain the esoteric meaning of dramatic celestial events such as eclipses and the appearance of comets.

In this module we are concerned with how astronomy dealt with the problem of defining a specific time in the year, a reference point in the cycle of the seasons.

Credit: didaktik.physik.uni-due.de

Credit: didaktik.physik.uni-due.de

The Sun

One way to “measure” the time of year is to observe the height (altitude) of the Sun in the sky. A simple way is to put a stick in the ground and to watch its shadow. When at about midday the shadow is the shortest within one year of observations, it will be around midsummer, when the shadow is the longest, then you know it is around the middle of winter. The position of the shadow also tells you the time of day. Essentially this is a sundial and they go back as far as 1500 BCE. More...

The Stars

With the stars there are other ways of judging the time of year. The visible stars change position slightly from night to night and they move around the sky throughout the year. Different constellations are visible at different times of the year. This also depends on where you are on Earth and each local civilisation used there “own” stars and constellations. But for several reasons, both practical and spiritual, there was a need to be more precise in knowing the time in the year.

Credit: Gilbert A. Esquerdo (Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, and Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (edited)

Credit: Gilbert A. Esquerdo (Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, and Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (edited)

It is striking that many civilisations throughout the world have applied the same technique, utilising what is called the heliacal rising of celestial bodies, to define a specific time of the year with a precision of a few days.

This technique observes when a certain star or constellation is visible for the first time in the year, just before sunrise. Which stars to use depends on the location on Earth, and sometimes people were interested in different parts of the season, but the basic technique has been the same.

The New Zealand Māori have traditionally used this method to define the start of the New Year.

They observed the heliacal rising of Matariki, the open cluster generally called Pleiades.

Solar and Sidereal day

First we must explain the difference between the motion of the Sun and the stars.

First we must explain the difference between the motion of the Sun and the stars.

Every day that the Earth rotates once about its axis, it also moves a bit further along its path around the Sun. It takes about 365 days or 360 degrees for a complete orbit around the Sun, so in one day the Earth will move about one degree in its orbit. This means that the Sun, as we see it from Earth, moves in the sky slightly differently from the stars.

The diagram shows that after one full rotation of the Earth, the same stars will be at the same location in the sky. But as seen from Earth, the Sun is lagging behind a little and the Earth must rotate a bit (one degree) further before the Sun is at the same position where it was the day before.

As a consequence, the stars rise each day about four minutes earlier than the Sun. The period that it takes a star to return to the same position in the sky is called a Sidereal day, and for the Sun that is a Solar day. A sidereal day is thus about 4 minutes shorter than a Solar day. This is the reason why every day at the same time, new stars rise above the horizon.

Credit: lpi.usra.edu

Credit: lpi.usra.edu

Throughout a whole year we see the entire sky passing by and this explains why we see different stars and constellations at different times of the year.

A different part of the night sky is visible from the dark side of the Earth, throughout the year.

|

4 Minutes each night 360 degrees rotation takes the Earth 24 hours. |

Heliacal Rising

Photo: flickr.com/photos/rachelpennington Just before Sunrise each day, the light of the Sun will wash out the sky and we cannot see the stars anymore. But because the stars are rising 4 minutes earlier every day, at some day we will be able to see a star that we could not see before, just before the Sun washes out our view to the stars. That day is the heliacal rising of that star.

Photo: flickr.com/photos/rachelpennington Just before Sunrise each day, the light of the Sun will wash out the sky and we cannot see the stars anymore. But because the stars are rising 4 minutes earlier every day, at some day we will be able to see a star that we could not see before, just before the Sun washes out our view to the stars. That day is the heliacal rising of that star.

After that, the star will be visible a little bit longer every day, until about half a year later, it will set in the western sky just before sunrise. The term Heliacal comes from the Greek “Heliakos” meaning “solar”, “of the sun”. In this context it means "close to the Sun".

Heliacal rising of Matariki

In New Zealand, Matariki has its heliacal rising in late June, which in the southern hemisphere means close to the winter solstice on about the 22nd June. This solstice is generally called the summer solstice, but that is only valid on the northern hemisphere. The seasons are opposite north and south of the equator. (See our EBook or Course “The Rhythmic Sky”).

Matariki in 2009 Frames generated with Skymap Pro This animation shows how Matariki rises just before the Sun every morning in the period 5 June until 25 June 2009 as seen from the position Christchurch, New Zealand. This is at astronomical twilight when the Sun is still 18 degrees below the horizon (about 6:20 am Local NZ Time). The Sun is the yellow dot at the bottom right on the solid white line, the ecliptic. You can clearly see how the stars rise a little bit earlier every day with respect to the Sun.

Frames generated with Skymap Pro This animation shows how Matariki rises just before the Sun every morning in the period 5 June until 25 June 2009 as seen from the position Christchurch, New Zealand. This is at astronomical twilight when the Sun is still 18 degrees below the horizon (about 6:20 am Local NZ Time). The Sun is the yellow dot at the bottom right on the solid white line, the ecliptic. You can clearly see how the stars rise a little bit earlier every day with respect to the Sun.

Matariki is indicated by the red circle in the first and last frame of the animation.

On 15 June it crosses the horizon at that time in the morning. It is difficult to define the time of heliacal rising accurately, because when the cluster is first seen, also depends on the eye sight of the observer, and on atmospheric and weather conditions.

Note that the constellation Orion (to the right) rises at about the same time as Matariki. The Great Hunter is still chasing the Seven Sisters. The Hunter is upside down in this southern hemisphere view.

Note also that on the 18th June the Moon appears in the top left of the image. It is visible until it disappears below the horizon on the 22nd June. The New Moon is when the Moon passes the Sun on 23rd June. For most Māori the New Moon is the start of the New Year.

In 2009 this heliacal rising is made more spectacular by the presence of three rocky planets. Venus and Mars are clearly visible at about 20 degrees over the horizon, while Mercury will stay closer to the horizon and disappears on the 23rd June.

A star will appear for the first time in the pre-dawn sky approximately one year after its previous heliacal rising.

Therefore the heliacal rising of any star will, dependent on the location on Earth, define one particular day during the year, and therefore this principle has been used by many cultures as a way to define their calendar.

In practice it will often not be possible to be as accurate as one day, because of varying atmospheric conditions and of course the weather. But this technique will be accurate to a few days, especially on locations where one has a clear view of the horizon. And that is certainly no problem in the Pacific.

Helical Rising in other cultures

Heliacal risings have been very important for the calendars of many civilisations, as they helped to define points of reference for the progressing year. Bright celestial objects that rise and set, and thus have a time in the year that they rise just before the Sun at dawn, were used in many ancient calendars.

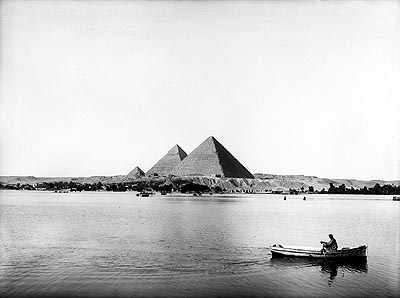

Photo: touregypt.net

Photo: touregypt.net

Egypt

The River Nile flooded every year covering the land with fertile mud and preparing it for the sowing and growing period. The harvest time started at the end of February and ended with the new Nile flood in July.

As it happened the heliacal rising of Sirius (Sothis) turned out to be a reliable predictor of the flooding of the Nile, which was such an important event in the life of the Egyptians.

Sirius also defined the exact length of the year between two consecutive helical risings. The first new moon following the reappearance of Sirius defined the first day of the New Year for the Egyptians.

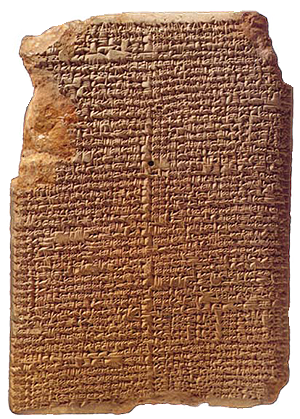

Mul Apin tablet.

Mul Apin tablet.

Credit: geocities.com/astrologymulapin

The ancient Babylonians included dates of heliacal risings on the Mul Apin tablets (image), which counted the number of days between heliacal rising of many stars. Essentially this creates a calendar when only one heliacal rising is observed, the others can be accurately predicted.

The Sumerians and the ancient Greeks are also known to have used the heliacal risings of various stars for the timing of agricultural activities.

Aztecs

The ancient Aztecs of Mexico and Central America also based their calendar upon the Pleiades. Their year began when priests first observed the heliacal rising of the cluster, similar to the tradition among the New Zealand Māori.

Māori Astronomy

Credit: taimaui.org, courtesy of Herb Kawainui Kane

Credit: taimaui.org, courtesy of Herb Kawainui Kane

There is little doubt that throughout human history, the Tangata Pasifika were the most excellent celestial navigators. They had to be! While living on such tiny specs of islands in the middle of a vast ocean that spans one third of the entire planet, navigation at sea was an essential survival skill.

Stars and constellations were intensively used for this purpose at night and the Sun during the day. They had other means as well such as ocean currents, prevailing winds, reflection waves, cloud formations and the occurrence of seaweeds, behaviour of sea birds, etc. But celestial navigation must have been the core of their skills to find their destination, and even more importantly, the way home.

The rising or setting of celestial objects, depending on the time of year gave directions on the horizon. Among the circumpolar stars and constellations, the Southern Cross gave a direction, depending on the time of year and how it was oriented in the sky.

Celestial objects were also important as markers of the seasons, and the heliacal rising of the Pleiades (Matariki) or Rigel (Puanga) were the key objects that related to identifying mid-winter or the beginning of the Māori New Year.

|

|

| Southern Cross (Mahu-tonga) above horizon (centre of image) |

Matariki "Eyes of God" |

Matariki tradition

Credit: tangatawhenua.com The Pleiades are among the celestial objects that were very significant for navigation in the Pacific. Naturally such objects had also spiritual and religious meaning.

Credit: tangatawhenua.com The Pleiades are among the celestial objects that were very significant for navigation in the Pacific. Naturally such objects had also spiritual and religious meaning.

As it happens in the South Pacific, this cluster does have its heliacal rising close to midwinter, and the fact that it is close to the ecliptic and thus rises at almost the same point where the Sun appears a short time later, has undoubtedly added a lot of significance to this event for Māori. At that time of year the Māori name for this star cluster is Matariki. Its heliacal rising is significant to define the beginning of the Māori New Year, hence Matariki celebrations are essentially the welcoming of the New Year.

Māori culture has always been a Lunar culture and the phases of the Moon have been very important throughout the year. For the Māori New Year (Te Tou Hou) the actual start is at the first New Moon after the heliacal rising of Matariki. Some tribes refer to the first full Moon. Yet other tribes did use the heliacal rising of other celestial objects such as Puanga (Rigel) the second brightest star in the Orion constellation.

Matariki celebrations actually ran for a whole month until the next new (or full) Moon.

Matariki literally means the The Eyes of the God (Ngā Mata o te Ariki). The god is Tāwhirimātea.

When Ranginui, the sky father, and Papatūānuku, the earth mother were separated by their offspring, the god of the weather, Tāwhirimātea, became angry, tearing out his eyes and hurling them into the heavens.

Copyright: Ngā Whetū Resources

Copyright: Ngā Whetū Resources

The nine stars of Matariki

In Māori tradition there are nine stars (Ref):

- Matariki (Alcyone) – the mother of the other stars in the constellation. Rehua (Antares) is the father but is not considered part of the Matariki constellation.

- Pōhutukawa – connects Matariki to the dead and is the star that carries our dead across the year (Sterope/Asterope).

- Tupuānuku – is tied to food that grows in the ground (Pleione).

- Tupuārangi – is tied to food that comes from above your head such as birds and fruit (Atlas).

- Waitī – is tied to food that comes from fresh water (Maia).

- Waitā– is tied to food that comes from salt water (Taygeta).

- Waipunarangi – is tied to the rain (Electra).

- Ururangi – is tied to the winds (Merope).

- Hiwaiterangi/Hiwa – is the youngest star in the cluster, the star you send your wishes to (Celaeno).

The best resource is the book Matariki: The Star of the Year by Rangi Matamua, available here

Listen to the podcast "Matariki and Maori astronomy with Dr Rangi Matamua" here.

Māori New Year

Declining tradition

The old Māori tradition of celebrating Matariki as the New Year gradually dwindled towards the 1940’s, probably also under influence of the Second World War.

A Mr. Harry Dansey reports in The New World - Te Ao Hou of the National Library of New Zealand -Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa (December 1967), an account from the late Mr Rangihuna Pire, of South Taranaki, who told him in 1957—he was then in his 70's—that he used to be taken by his grandparents to watch for Matariki at night in mid-winter. “That was at Kaupokonui, in South Taranaki. The old people might wait up several nights before the stars rose. They would make a small hāngī. When they saw the stars, they would weep and tell Matariki the names of those who had gone since the stars set, then the oven would be uncovered so the scent of the food would rise and strengthen the stars, for they were weak and cold”. This must have been in the late 1880's or early 1890's. Ref...

A Mr. Harry Dansey reports in The New World - Te Ao Hou of the National Library of New Zealand -Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa (December 1967), an account from the late Mr Rangihuna Pire, of South Taranaki, who told him in 1957—he was then in his 70's—that he used to be taken by his grandparents to watch for Matariki at night in mid-winter. “That was at Kaupokonui, in South Taranaki. The old people might wait up several nights before the stars rose. They would make a small hāngī. When they saw the stars, they would weep and tell Matariki the names of those who had gone since the stars set, then the oven would be uncovered so the scent of the food would rise and strengthen the stars, for they were weak and cold”. This must have been in the late 1880's or early 1890's. Ref...

An ancient annual custom of Māori during the observation of Matariki was to mihi maumahara —pay acknowledgement to the passing on of those who have left us from this world. Their wairua travels up into the entranceway of the heavens through Matariki, to join the many other ancestors who have become stars in the sky—Kua wheturangitia ratou ki tua ki te Aara I Tiatia. Ref...

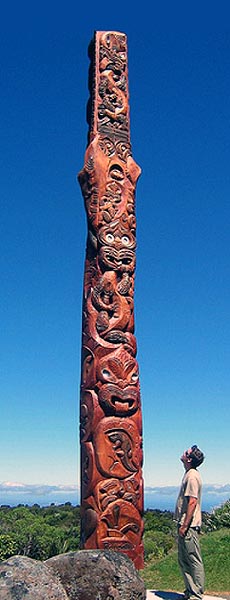

Pouwhenua.

Pouwhenua.

Photo: Robinvanmurik/flickr

Revival

New Zealand is a multicultural nation of settlers. The Māori (Tangata Whenua) arrived around approximately 800 years ago from Pacific Islands to the north. Pākehā started to arrive as occasional visitors in the 17th century and as settlers in the 19th century. In modern times immigration continues under strict immigration rules, and the population of New Zealand becomes increasingly more multi-cultural, with in particular growing representations from Oceania and Asian countries.

As an aspect of the new Millennium, the first modern Matariki celebration was organised in Hastings (New Zealand) in the year 2000. This marked a revival of the tradition, that draws more people to celebrations ever since, in many places around the country each year. It now has become a widely recognised event each year around mid-winter, although it is unfortunately not always properly related to the Māori traditions around this event.

Mid Winter

Baltray standing stone, County Louth, Ireland,

Baltray standing stone, County Louth, Ireland,

at sunrise on midwinter's day.

Photo: independent.ie

Matariki as the traditional Māori New Year is an example of the celebration of midwinter, as it has been and still is being celebrated in many forms all over the world. It is the celebration that the shortest day has gone and that light returns. It is looking forward to a new year that lies ahead and at the same time a celebration and reflection of and on the past, the ancestors, the relatives that have passed away, etc. But on the southern hemisphere, midwinter or the winter solstice is around 22 June, and not 22 December as on the Northern hemisphere.

Midwinter has probably been the most intense celebration during the year for many ancient cultures. Especially in areas with rugged climates, winter was a time of hardship, with famine, storms and low temperatures. In mythology winter was often related to a struggle of light over darkness, and the winter solstice was welcomed as the point after which the days were getting longer.

Sankta Lucia

In colder climates, midwinter was the last feast before deep winter began. Most cattle were slaughtered so they would not have to be fed during the winter, and it was the only time of the year for some, that a supply of fresh meat was available. It was also a time that little work could be done on the land that lay bare, so it was a time for reflection and for sharing with others. Even in modern times these attitudes are still valued for spiritual comfort, having something to look forward to at the darkest time of the year.

Sankta Lucia in Sweden

Sankta Lucia in Sweden

Yule

Yule

is a winter festival that was celebrated by the ancient Germanic people in Europe as a pagan religious festival around midwinter.

In the 4th century the Christian church adopted the Yule celebrations as the equivalent of the Christian festival of Christmas and placed it on December 25 on the Julian calendar. This date is likely chosen to coincide with the winter solstice and with the existing pagan celebrations.

Pleiades, M45

Photo: John Drummond, (edited)

Photo: John Drummond, (edited)

possumobservatory.co.nz New Zealand Māori have used the heliacal rising of the Open Cluster the Pleiades. Māori give the name Matariki to this cluster only in about June each year when it is connected to the Māori New Year (more below). This clearly visible cluster has been significant in many cultures and mythologies throughout the world.

Not only is it a beautiful and distinct object in the night sky, in which on a clear night seven or more individual stars can be seen with the naked eye, but it also lies close to the ecliptic, in the constellation Taurus, and can be seen both from northern and southern latitudes most of the year.

The Pleiades, also known as Messier object M45, contain more than 3000 stars. The Open cluster is at a distance of about 400 light years, and is 13 light years across.

In Greek mythology, Atlas and Pleione have seven daughters: Maia (eldest), Electra, Taygete, Alcyone, Celaeno, Sterope (aka Asterope), Merope (youngest). The seven sisters were fancied by the great hunter Orion. He pursued them for seven years, until Zeus saved them by transforming the seven sisters into doves, placing them among the stars. In the sky Orion continues to pursue them for eternity.

| The twelve brightest stars in M45 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Name | Catalogue | Magnitude |

| Alcyone | Eta / 25 Tauri | 2.90 |

| Atlas | 27 Tauri | 3.62 |

| Electra | 17 Tauri | 3.70 |

| Maia | 20 Tauri | 3.87 |

| Merope | 23 Tauri | 4.18 |

| Taygeta | 19 Tauri | 4.30 |

| Pleione | 28 Tauri | 5.09 |

| HD 23985 | 5.23 | |

| HD 23753 | 5.44 | |

| Celæno | 16 Tauri | 5.46 |

| 18 Tauri | 5.64 | |

| (A)sterope 1 | 21 Tauri | 5.80 |

Credit: HST, NASA

Credit: HST, NASA

Under very clear conditions about 12 stars are visible with the unaided eye, but generally this will be about 9 or less.

Tūmanako - Prospect

Matariki is becoming more popular not only because it celebrates Māori culture, but also because it can bring all New Zealanders together around general values that are typically celebrated at midwinter.

It is a time of contemplation, looking back to the past and valuing one’s own ancestral background, giving thanks for everything accomplished during the past year and looking forward to the new year and the distant summer season with its promises. It is also a time of giving and sharing among whānau and community groups.

Multi Cultural diversity

Te Papa 2008

Te Papa 2008

From 2022, Matariki will be a public holiday in New Zealand celebrated on a Monday or Friday close to the appropriate date according to Māori tikanga. We do hope that this will not only be a celebration of Te Ao Māori, as it must be, but also celebrates the rich multi-cultural diversity that New Zealand has. Ultimately it could be the celebration of being a member of a vibrant multi-cultural society, where we value and respect the diversity and colourfulness of different cultural heritage.

A modern revival based on the rich tikanga of the Tangata Whenua.

-

-